Kowree Biolink

Click here to view the Kowree Biolink photo Gallery

The Kowree Biolink started as a “vague idea over a glass of port”, as all good ideas do. The idea was to create a habitat corridor, to link fragmented habitat caused by agricultural clearing, from the river to the desert. This idea took shape with a successful grant from the National Heritage Trust and the knowledge, experience and dedication of the members of the Kowree Farm Tree Group at the time.

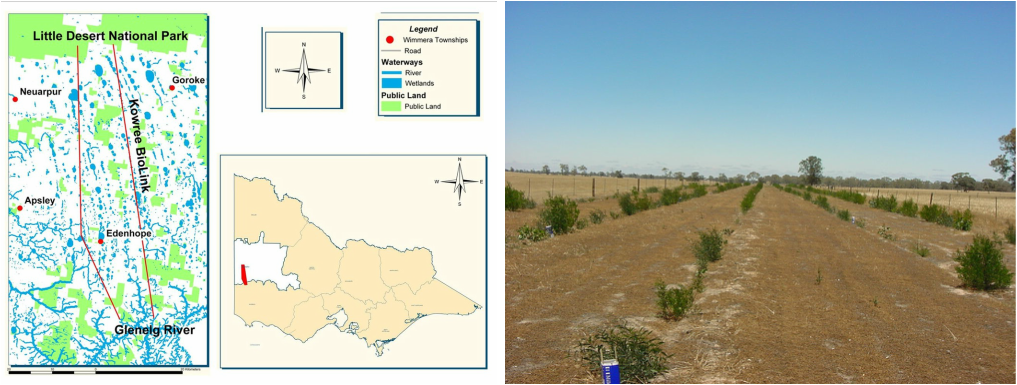

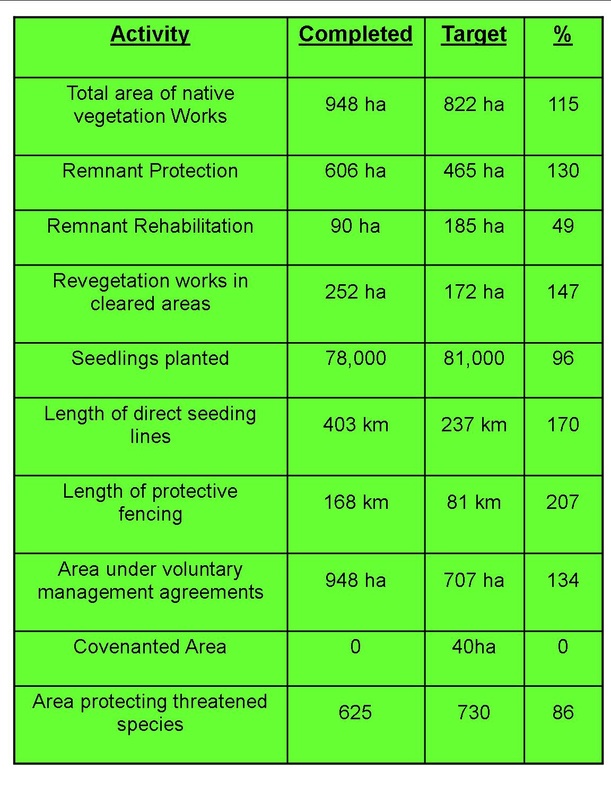

The project took over four years, involved over 350 people, created 168km of fencing and saw around 78,000 seedling planted and 643km of direct seeding. Along the way 696km of remnant bush land was protected and enhanced. The total effect was the establishment of corridors, protected wetlands and remnant vegetation on seventy farms to link the Glenelg River to the Little Desert, a total area of 948ha.

The project showcased what can be achieved with the right mix of knowledge and experience in revegetation and good facilitation to inspire farmers and support them to get the job done.

So how was a 14km wide 70km long biolink corridor along the Edenhope-Kaniva and Edenhope-Casterton road achieved?

Well the success really began with the approach. The focus of the project was to link remnant patches of stringy bark forest in order to improve and extend the habitat for the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo and other species of birds and mammals. To achieve this goal a “cup of tea and a flyer” method was used. Rather than attracting farmers through widespread advertising, farmers with potential habitat were approached individually.

Each project began with the landholder’s perspective in mind. In some cases it may have been to create a realistic plan to achieve that impossible dream of protecting an area of remnant vegetation, or to integrate a biodiversity goal in the productive form of a shelterbelt. Projects were made flexible in order to achieve the goals of the farmer, whilst also creating a habitat link. This approach meant that the biolink was popular and achieved a high profile, through word of mouth, leading to a greater number of projects being undertaken.

Once a project was started farmers were provided with ongoing support to get that project done. This may have been in the form of a phone call when it was time to spray and rip and site in preparation or time for planting, or though more practical support such as ordering and delivering seedlings or arranging contractors to rip and direct seed. A key part of the success was that a facilitator living in the district was able to recognize the difficulties individual farmers might have with parts of the project and gave them gentle reminders so jobs weren’t forgotten or helped in finding assistance to ensure jobs were completed at key times.

The support given to the farmers to achieve their project goals widened the biolink project to include a greater number of people. School children and volunteers were involved in planting seedlings and other tasks, increasing the impact the Kowree biolink had on the overall community. The project involved volunteers from Green Corps and Conservation Volunteers, who were able to give assistance with fencing and planting when required.

Finally a great deal of success lies in the time frame of the project. A project running over four years gives time for word of mouth to spread and for a project’s popularity to build. It also allowed time for projects to be fully completed, rather than being left unfinished as time ran out.

Overall the project showed that large conservation goals can be achieved through utilizing the knowledge, experience and passion that lives within rural communities.

In 2003 the Kowree Farm Tree Group was awarded the Bushcare Nature Conservation Award for it's biolink project.

return to home page

The project took over four years, involved over 350 people, created 168km of fencing and saw around 78,000 seedling planted and 643km of direct seeding. Along the way 696km of remnant bush land was protected and enhanced. The total effect was the establishment of corridors, protected wetlands and remnant vegetation on seventy farms to link the Glenelg River to the Little Desert, a total area of 948ha.

The project showcased what can be achieved with the right mix of knowledge and experience in revegetation and good facilitation to inspire farmers and support them to get the job done.

So how was a 14km wide 70km long biolink corridor along the Edenhope-Kaniva and Edenhope-Casterton road achieved?

Well the success really began with the approach. The focus of the project was to link remnant patches of stringy bark forest in order to improve and extend the habitat for the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo and other species of birds and mammals. To achieve this goal a “cup of tea and a flyer” method was used. Rather than attracting farmers through widespread advertising, farmers with potential habitat were approached individually.

Each project began with the landholder’s perspective in mind. In some cases it may have been to create a realistic plan to achieve that impossible dream of protecting an area of remnant vegetation, or to integrate a biodiversity goal in the productive form of a shelterbelt. Projects were made flexible in order to achieve the goals of the farmer, whilst also creating a habitat link. This approach meant that the biolink was popular and achieved a high profile, through word of mouth, leading to a greater number of projects being undertaken.

Once a project was started farmers were provided with ongoing support to get that project done. This may have been in the form of a phone call when it was time to spray and rip and site in preparation or time for planting, or though more practical support such as ordering and delivering seedlings or arranging contractors to rip and direct seed. A key part of the success was that a facilitator living in the district was able to recognize the difficulties individual farmers might have with parts of the project and gave them gentle reminders so jobs weren’t forgotten or helped in finding assistance to ensure jobs were completed at key times.

The support given to the farmers to achieve their project goals widened the biolink project to include a greater number of people. School children and volunteers were involved in planting seedlings and other tasks, increasing the impact the Kowree biolink had on the overall community. The project involved volunteers from Green Corps and Conservation Volunteers, who were able to give assistance with fencing and planting when required.

Finally a great deal of success lies in the time frame of the project. A project running over four years gives time for word of mouth to spread and for a project’s popularity to build. It also allowed time for projects to be fully completed, rather than being left unfinished as time ran out.

Overall the project showed that large conservation goals can be achieved through utilizing the knowledge, experience and passion that lives within rural communities.

In 2003 the Kowree Farm Tree Group was awarded the Bushcare Nature Conservation Award for it's biolink project.

return to home page